Nathan Altman: Artist Yeshiva – Chanukah Edition

While Judaica has oft-favored the Menorah, with its many artistic permutations (from the rustic feel of ANK ceramics, through the whimsy of Susan Alexandra, to the sleekness of Via Maris, the nobility of your grandmother’s simple silver option notwithstanding), Hanukkah offers us another Jewish object to hold and behold; to pore over and pour out of. This Hanukkah, Jews at large are invited to reclaim the Menorah’s simpler, steadfaster cousin—the unassuming oil jug.

It is the hope hidden in dark times. It is abundance in the place of meager rations.

With no formal rabbinic decree that every Jewish home place a jug of oil in their window in the late days of Kislev, our models for this powerful symbol must leave the realm of “able to be purchased at the local Judaica emporium” and enter the world of symbol and myth. With no formal rules of what a Hanukkah jug must be (as Menorahs have for height, spacing, design), all jugs are permissible. Suddenly, the home is full of this oily and alluring possibility—the coffee pot’s brew could prove eight-times more energizing than normal, the mascara tube could make fluttered lashes eight-times more seductive than average, and the watering can’s gentle rain could bring forth a garden eight-times more colorful and fragrant than thought possible. In recentering the jug, the work of Nathan Altman comes to mind, celebrated cubist, Avant-Garde painter, sculptor, illustrator, and theater-artist, as well as propagandist;

Hopefully, a deeper look at his jugs, bottles, and pitchers will remind every Jew to cast an eye to our own vessels this Hanukkah, to pay deeper attention to the miraculous possibility already adorning our tables and our sinks.

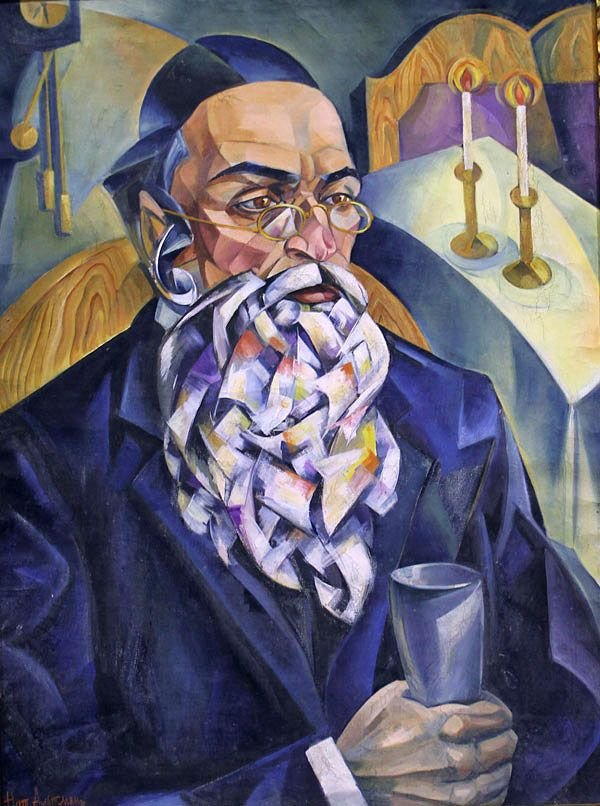

Nathan Altman, Portrait of a Young Jew, 1916

Nathan Altman was born 1889 in Vinnytsia, Ukraine, which was then a part of the Russian Empire. His father died of tuberculosis when Nathan was quite young, and his mother fled the pogroms, leaving him in the care of his grandmother. He began formal training at the Odessa art school at only 13 years old, had his first exhibition at 15, and by 18, during a stint in Paris, fell in with the Avant-Garde crowd who were to be his contemporaries all his life, among them, Marc Chagall. He attached himself to the “Montparnesse School”, also known as the “School of Paris”, a term coined by André Warnod, who were a motley assortment of French and immigrant artists, mostly Jewish, working in Paris before the First World War. Their school of overlapping post-Impressionism, cubism, and fauvism was lead by Picasso and Matisse. In this environment, Altman was exhibited by the Salon of the National Society of Fine Arts in Paris, achieving demonstrable success in fine art. He then returned to Ukraine, and began painting works that more directly expressed his Jewish heritage. These are Jewish Funeral Ceremony, painted after his grandfather’s passing, and Jewish Graphics. Even as he traveled back and forth to Paris as well as St. Petersburg (where he struggled, as a Jew, to obtain a residential permit), his work maintained a Jewish focus. His Portrait of a Young Jew, showing his deftness as a sculptor, is a self-portrait done as though he was a Hasid. He also maintained a strong theatrical presence, producing and designing for the Yiddish theater, and seeing works of Shalom Aleichem come to life on stage and screen (with greats like Granovsky and Babel).

Altman, like many artists of his period, took a strong revolutionary stance. He worked in a futurist style at times, and championed the rights of people and laborers. During this time, he became one of the guiding figures of Constructivism, the abstract and stern usage of artistic motif for political gain. Lenin even commissioned a portrait from him. Over time, this work became coercive—his artist friends were being killed for dissent, and he was forced to design banners for Stalin, the man who was killing them. He absconded to Paris in 1928, gave up his early-Bolshevik idealism, and took up drawing anti-fascist cartoons. At this point, he paused fine art for good. A few successes later (a theatrical production of Hamlet, a cinematic production of Don Quixote, an award for Honored Artist of Russia in 1968), and Altman passed in 1970.

Jug and Tomatoes

The jugs were painted in various years, from his early days in Paris to his time under a slowly simmering communist rule. The first, Jug and Tomatoes, 1912, is a dreamy, post-impressionist marvel. Thick brushstrokes and vivid colors offer up a triumphant image of the jug, the sort of reflective blue miracle-holder that could signal the end of a war and the promise of days to come.

The deep color of the jug is used to darken the composition’s shadows, allowing the jug to respond to the tomatoes, cucumber, and pleats of cloth, to be answer to their shaded question. This is a jug that knows it has darkness-dispelling oil within it, which is certain of its capacity to outshine anything overcast.

Colored Bottles and Planes

The 1919 Still Life, Colored Bottles and Planes, gives us an entirely different understanding of the jug archetype. Leaning away from the earlier almost-fauvism, A Still Life shows a cubist sentiment done without cubist abstraction—harsh lines and angles are rendered without sacrificing the realism and integrity of the piece. The effect is dramatic and austere.

These bottles, with only a little liquid left, like our storied jug, are depicted with extreme importance and severity, but the pervasive mood responds to this urgency with hopelessness—mottled colors, listless shapes, a composition shattered and seemingly falling apart. In our oneiric imaginings of the Hanukkah jug, this could be a model of the jug, once found: brutally important, and obviously not enough. This image shows the moment before the miracle, when harsh reality asserts itself and lack is made manifest.

Still Life with a White Jug

Still Life with a White Jug, as Altman enters a period of propaganda and Constructivism, emerges powerfully shaped against a more early-period feathered background. On the right hand side, the jug is shaded, providing heft and form, while the left hand side shows pure white, unreal, leaving the viewer with the image of an object melding between actual presence and pure symbolism.

This jug knows that the Hasmoneans will become Hellenizers themselves, knows that freedom, like the kind offered by the Bolsheviks, soon becomes a facsimile of itself. That real leadership can blur into disappointing figureheads. Or, this image is the symbol lasting where the actual jug stops—the ninth day of Hanukkah, when the miracle is finished but its impact perseveres.

Still Life, 1923

The final jug, Still Life, 1923, is a return to the post-Impressionism Altman began with, and a far cry from his angled skyscrapers and Russian propaganda pieces of that period. The bottle rests on a precarious-feeling table, atop a bright handkerchief and beside a bright bowl of candy. The brushstrokes are visible, messy, figurative, and the cork has popped and been reinserted.

The prevailing mood is one of hasty, happening, life: opened bottles, rumpled cloths, shadows soft and unassuming, colors full and pronounced.

It’s associated miracle also occurs in complicated life—this jug, unstopped and recorked, brings an awareness of the still-enduring miracle of Hanukkah, the riches already tasted that will continue to be enjoyed again and again. This piece’s tidy devotion (candy like an offering on a re-anointed altar) bespeaks a happy invitation to drink, to eat, to be merry at the table of your forefathers, to shine a little light out of your family’s window. This jug hold the Hanukkah miracle of childhood, of never-ending Gelt chocolate coins, of an old story, opened yet unfinished, ready to be poured out.

While strangers won’t see it from your window, and your family won’t smell it frying from your kitchen, and children won’t spin it on your floor—the Hanukkah jug, like the work of Nathan Altman, is underrated, Jewish, timeless, and eminently interpretable.

The Hanukkah jug is what you didn’t know your heritage already had waiting for you. And Hanukkah wouldn’t be Hanukkah without it.

Nathan Altman, Costume design for “The Dybbuk”, 1922